Introduction and challenges

Millet is considered the 6th most important cereal in the world. It is a robust cereal crop and an important staple of the African semi-arid tropics. It is mostly grown for food (fl our processed into fermented and unfermented products), but also for beer making and animal feed. Nine species are common in Sub-Saharan Africa, but only four are grown on a signifi cant scale: Pearl or candle millet (Pennisetum glaucum), Finger millet (Eleusine coracana), Teff (Eragrostis teff) and Fonio (Digitaria exilis and Digitaria iburua). Pearl millet is by far the most important, by cultivated land area, due to its high yield potential under drought and heat stress. Finger millet is also common in Eastern and Southern Africa; Fonio only in West Africa, while Teff is only grown in the dry mid-highlands of Ethiopia where it contributes about 25 % of total national cereal production.

Millet is known for its very wide adaptability to different growing conditions and its tolerance to dry spells, drought and heat. The crop is mostly grown in areas, where rainfall is low and irregular, and where other crops such as maize or sorghum have failed as it has great potential to avert hunger and/or famine in harsh climates. As the world becomes drier and hotter, millet may attain more importance as a staple food crop. This is more so in Africa where desertifi cation levels are increasing and threatening food security.

Pearl millet contains more protein and minerals than most other cereals. It contains more than three times the iron content of maize and would thus be an important dietary component particularly in view of the high prevalence of iron defi ciency among many populations in Africa, particularly women. Compared to sorghum, pearl millet is also reported to have better digestibility properties. Due to its high nutritional properties, pearl millet is used to prepare some traditional weaning foods.

Main challenges associated with millet production and utilization

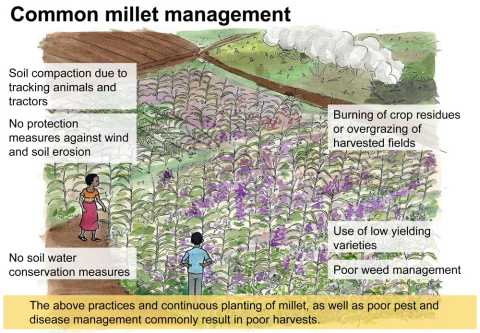

The main challenges to millet production in Africa are declining yields, which are mainly due to short and unreliable rainy seasons with frequent dry spells, droughts, declining fertility of soils and poor crop management. The yields of millet range between 500 and 1500 kg per hectare, but can be as low as 150 kg per hectare. The low yields are also partially due to the crop’s low harvest index (less than 20 %), but it is also due to the circumstance that millet is mostly cultivated on poor soils with no or very little inputs. However, if soil fertility is adequate and the required rainfall amount is received (or irrigation applied), millet can reach 3000 kg per hectare or more. Other reports also suggest that millet production is declining due to the switch by farmers (and consumers) to other cereals such as maize due to the diffi culties associated with millet grain processing (e.g. hulling using traditional methods), taste preference. There are also views that the decline is partly due to the generally inadequate support to millet promotion from a research and policy point of view in many African countries.

Millet is regarded as a crop that has less pest and diseases problems than most other cereals; however, devastating diseases and pest attacks can also occur as elaborated in later sections.

Organic production practices

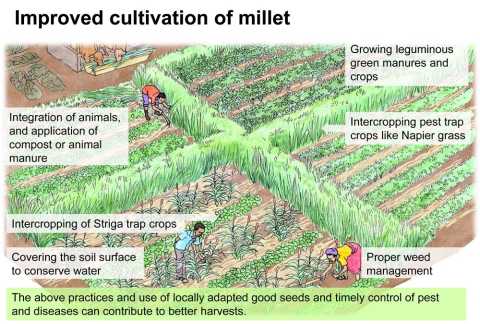

Pearl millet is generally regarded as a crop with few pest problems and rather low nutrient requirements. Nevertheless, it responds well to improved growing conditions. Best practices can increase yield and yield security of millet improving soil fertility, diversifying the cropping system, preventing weed competition, as well as major pest and disease problems.

Therefore, the objective of this guide is to encourage farmers to introduce the useful approaches, which can be adapted to the local conditions to increase yields and yield security.

Sources and recommended further readings

Publications:

- Sorghum and millets in human nutrition. FAO Food and Nutrition Series, No. 27). ISBN 92-5-103381-1

- Standards of the Codex Alimentarius for sorghum and pearl millet grains and fl ours. FAO/WHO Food Standards Programme.

- Lost Crops of Africa: Volume 1: Grain. National Academy Press 1996. Washington D.C.

- Norman M.J.T, Pearson C.J; and Searle. 1995. Ecology of Tropical Crops. Cambridge University Press. 430pp

- Purseglove, J.W. 1988. Tropical Crops. Monocotyledons. Longman Group UK Ltd, Longman House, England. 607pp

- Andrews, D.J. & Kumar, K.A., 2006. Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R.Br. In: Brink, M. & Belay, G. (Editors). PROTA 1: Cereals and pulses/Céréales et légumes secs. [CDRom]. PROTA, Wageningen, Netherlands.

- Organic Farming in the Tropics and Subtropics, Naturland.

- D. Fatondji, C. Martius, C.L. Bielders, P.L.G. Vlek, A. Bationo, B. Gerard. 2007.

Effect of planting technique and amendment type on pearl millet yield, nutrient uptake, and water use on degraded land in Niger: In: Advances in Integrated

Soil Fertility Management in sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and Opportunities, pp 179-193

Useful weblinks:

- Cultivars, improved varieties: www.icrisat.org

- Common pests and diseases: www.infonet-biovision.org

- Production, post-harvest handling, economies, nutritional aspects: www.fao.org

Comments

Post a Comment