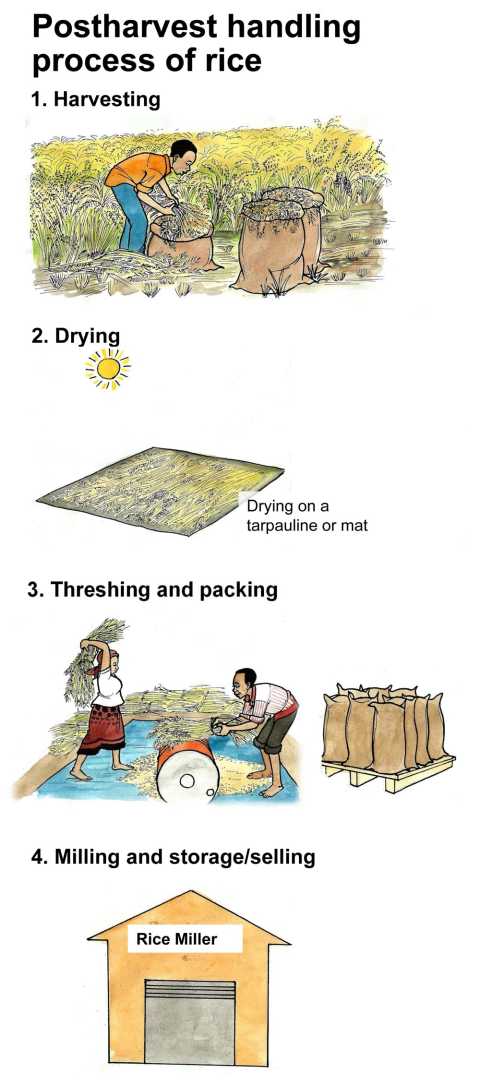

Minimising postharvest losses

Proper postharvest handling of rice aims at maximizing grain quality, minimizing losses and any contamination risks from extraneous materials and agents. Note: in case of certified organic rice production, maximum separation of organic, in-conversion and conventional rice throughout the handling process is also important.

The postharvest handling process starts with proper and timely harvesting, threshing, drying, milling, storage up to safe and secure packaging:

- Harvesting - Rice is ready for harvest when the grains are full-sized, hard and the panicles have bent down. The number of days from flowering to harvest is fixed for the varieties. This should be used to ensure timely harvest and reduce grain shattering. At this stage, most of the panicles have turned golden brown in colour. In order to prolong the shelf life, rice should be harvested only when it reaches full maturity. The date is chosen taking into consideration the stage of maturity, the shattering characteristics of the variety and the weather conditions (preferably during dry weather). Take care to avoid mixing weed seeds with the harvested rice grains, so any weeds with fully matured seeds can be removed prior to harvesting. Harvesting by cutting the stem of the rice close to the ground with serrated sickles is much faster than harvesting using knives. The harvested paddy should be put on tarpaulins or similar materials to reduce contamination with foreign materials such as stones.

- Drying - Rice is usually harvested when it has high moisture content and, therefore, needs immediate drying. Delays in drying or uneven drying will result in qualitative and quantitative losses by discolouration of grains, moulding, and will increase the risk of insect damage. The paddy should be spread evenly on the tarpaulin, and this should not be too thick as this will develop heat and cause discolouration. Drying under a cool, dry environment is preferred to fast drying of the grains under a hot sunny environment, which may affect the quality of the grain and break during milling.

- Threshing and Milling - Threshing methods range from simply beating the rice sheaves on a stone or piece of wood to the fully mechanized combine harvesting. The rice husk and the bran are separated by milling to obtain the edible seed. If the rice was not dried well before threshing then it should be dried again to about 14 % before milling. In the simple method, mostly used at the household or village level, rice is milled in a one-step milling process. However, proper milling facilities are required in order to achieve a higher percentage of whole grains for better quality and higher price. To fetch good prices, the milled rice must be whole grains and free of husks, weed seeds, stones and other foreign materials. Note: under certified organic production, the rice mill should be cleaned properly prior to milling organic rice. For example, five sacks of organic rice can be milled first to clean the mill and classified as conventional. Only the succeeding milled rice will be recognised as organic.

- Storage - Rice quality can be affected by temperature and air moisture. Different processed rice (wholegrain or white) require different storage conditions. For example, wholegrain rice can be stored for two years under airtight storage and moderate temperatures (10-35 degree Celsius) while white rice can be stored up to three years under the same conditions.

Increasing income from the rice production system

High dependence on rice alone is not only risky for the farmer, but often unsustainable.

Common to approaches of achieving a sustainable rice production system is to diversify the sources of income from the system. This is done by adopting other enterprises which are closely linked and complementary with the rice enterprise. This will eventually ensure that any risks that may affect the rice enterprise are well-buffered by the other enterprises. Then the total income received by the farmer will not be heavily affected.

a. Crop diversification especially in upland systems. By introducing leguminous crops as intercrops or rotation crops, or high value vegetable crops, such as garden eggs, okra, pepper, the farmer has extra crop to sell. The farmer should, therefore, carefully select the crops to introduce in the system. As a guide, the farmer should select crops that can be used as food for the household and any excess is able to be sold for income.

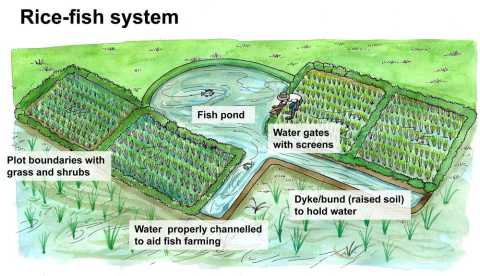

b. Introducing fish into the rice production system especially in the lowland systems, which are prone to flooding. A rice-fish system is an integrated rice field where fish is grown concurrently or alternately with rice. This system allows for the simultaneous production of fish and rice, without the reduction of the rice yield, while providing an additional source of income to the farmer. The field may be deliberately stocked with fish or the fish may enter the field with the irrigation water, depending on the locally available species.

This system is especially suited for rice production systems where farmers are not using chemicals.

Where water control is good, fish should be deliberately left to grow and is harvested just before the fields dry up. Research has also shown that performance of rice is significantly improved by the rice-fish polyculture compared to the rice monoculture. In principle, as long as there is enough water in a rice field, it can serve as a fish culturing system.

However, a rice field is by design intended for rice and conditions may not always be optimum for fish, for example whereas rice may survive long periods of standing water, fish may not. Thus, there is a need to make some modifications to rice fields in order to accommodate fish culture. This can be done in many ways, for example:

i. Increasing dike (bund) height - Rice field embankments are typically low and narrow since most rice varieties do not require deep water. To make the rice field more suitable for fish, the height of the embankment needs, in most cases, to be increased to a height of about 40-50 cm. This is sufficient to prevent most fish from jumping over.

ii. Provision of weirs or screens - To prevent loss of the fish stock with flowing water, farmers install screens or weirs across the path of the water flow, depending on the local materials available e.g. bamboo slats, a basket, a piece of fish net material or any well perforated piece of sheet metal.

iii. Provision of drains - The common practise for managing water levels is to temporarily break a portion of the embankment to let the water in or out at a convenient point. It is advisable to provide a more permanent way of conveying water in or out. Types of water outlets that can be installed include bamboo tubes, hollowed out logs or metal pipes.

iv. Fish refuges - A fish refuge is a deeper area provided for the fish within a rice field. This can be in the form of channels or several channels or ponds. The refuge will provide a place for the fish in case water in the field dries up or is not deep enough. It also serves to facilitate the fish harvest at the end of the rice season or to contain fish for further culture while the rice is harvested.

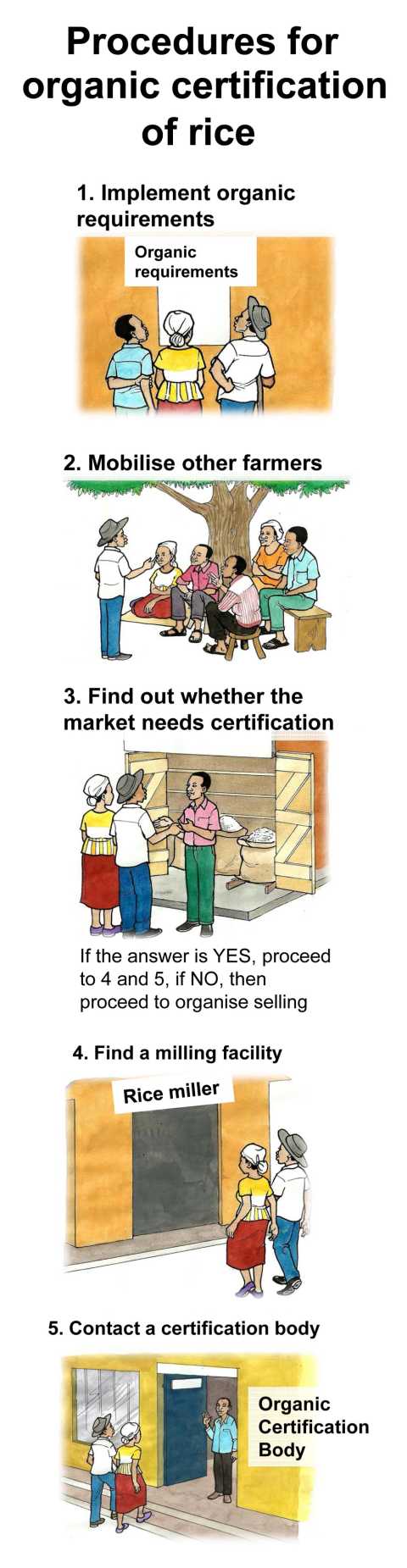

Marketing and organic certification of rice production

Organic certification of rice production is only reasonable if done as a market requirement, i.e. there should be a market that demands it. As the organic markets continue to grow in Africa both domestic and export markets, more rice producers will need to verify and approve their systems as organic. Thus certification is expected to increasingly become important.

In such a case, interested farmers should be willing to adopt the general organic production requirements, like no use of synthetic pesticides and fertilisers, treated and genetically modified seeds, as well as other sustainable production methods as discussed in the previous sections of this chapter. Farmers should be willing to learn and apply new knowledge to find organic solutions to any existing challenges to rice production.

Other considerations include:

- Farmers should have a sizeable amount of land to produce rice beyond the household requirement (commercial volumes) in order to be able to cover the extra costs of certification. The land should also be owned by the producers or they should have assured a long-term lease on the land.

- The producers should have access to at least one processing facility (especially for milling and packing), where they can negotiate for preferential treatment of their harvests to minimise contamination. Eventually as volumes increase, they can acquire their own processing facilities.

- A group of farmers of the same village, with adjacent fields can form a producer organisation of organic producers to minimise the risks of contamination from neighbouring fields. For organic rice, it is also important to avoid any contamination with conventionally grown rice and other substances during processing. All postharvest equipment used for handling conventional rice should be adequately cleaned before being used for organic rice. It is also very important to use clean sacks that have not been used for synthetic fertilizers or any chemicals, or sufficiently wash them before using them for harvested produce.

Email: Editor@agricinafrica.com

Comments

Post a Comment