Sweet Potato Summary Fact Sheet

Production

139,439 MT

FAOSTAT, 2020

73,940 Ha

FAOSTAT, 2020

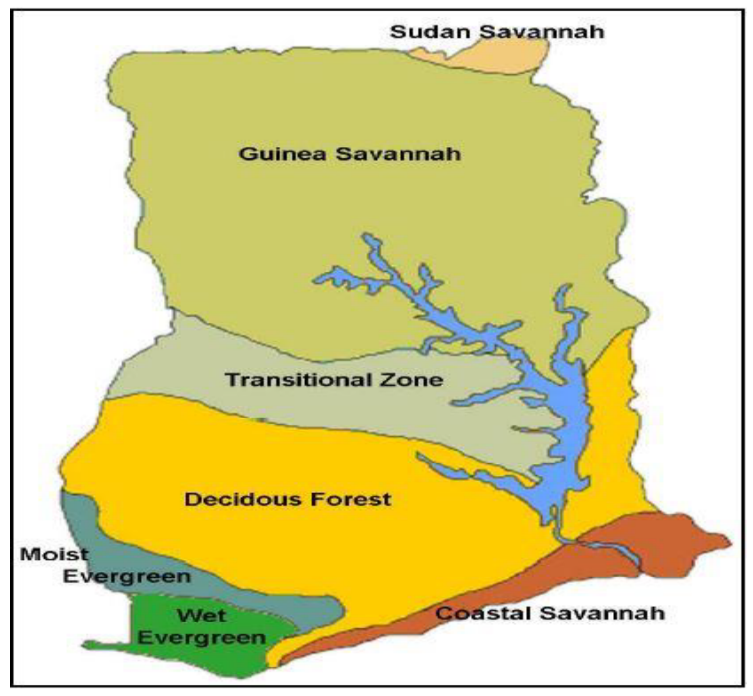

- Guinea Savanna Zone (December-March)

- Forest - transition and Coastal Savanna Zones (March-October)

- The crop can be cultivated twice in the Forest-transition and Coastal Savanna Zones.

- Can be cropped thrice in any agro-ecology using supplementary irrigation.

- Some farmers also take advantage of residual rainfall water and cultivate in valley bottoms.

1m x 1m (100cmx100cm)

Different recommended plant distances depending on the variety and locality.

- 100cm x 100cm (30,000 for mounds)

- 100cm x 100cm (33,333 for ridges)

- NPK

- NPK 12-30-17+0.4Zn

- NPK 15-15-15

- NPK 17-10-10

- Muriate of Potash

- Urea

- Organic fertilizer - Cow dung, Poultry manure and Compost

Recommended Blend (N-P2O5-K2O)

NPK 17-10-10 for Forest-Savannah Transition

NPK 15-15-15 (all ecologies)

NPK 12-30-17+0.4Zn (all ecologies)

- 6 bags of NPK per hectare or 25-30g of fertilizer per plant (apply as split; 4 weeks after planting and 8-12 weeks after planting (at the initiation of storage root development).

OR

- Apply 3-4 bags of NPK per hectare 4 weeks after planting and 1.5 bags of urea and 1 bag of Muriate of potash mixed as second application at 8-12 weeks after planting (at the initiation of storage root development). spot place fertilizer and cover.

- Organic fertilizer

- Cow dung – 3 tons/ha.

- Poultry manure – 4 tons per ha.

- Compost – 5 tons per ha

- Sauti,

- Santom pona

- Okumkom

- Faara

- Apomuden

- Otoo

- CRI-Ligri

- CRI-Patron

- AGRA-SP 09

- SARI-Nan

- CRI-Gavana

- Bell view potato

- Orleans potato

- Sakura

- Evangeline potato and

- Burgundy potato

Productivity

30,000 Kg/Ha (30 Mt/Ha)

1.88 Mt/Ha

FAOSTAT,(2020)

Budget Benchmarks

GHS 4,950.00

Amount involved in establishing a hectare of sweetpotato field (2021)

GHS 21,420

- Using a yield and computations of the farmers field (6.12 MT/Ha or 6,120 Kg/Ha).

- 2021 market price of sweetpotato costing GHS 3.5 per kg

GHS 16,470

Profit margins from the sales of establishing a hectare of sweetpotato field and deducting operational cost

Risks

- Alternaria leaf spot

- Leaf and stem blight

- Sweetpotato virus disease (SPVD)

- (Sweetpotato feathery mottle virus (SPFMV) and

- Sweetpotato chlorotic virus (SPCSV)

- Fusarium root and stem rot (Fusarium solani)

- Sweetpotato weevil (Cylas sp.)

- Striped Sweetpotato weevil (Alcidodes sp.)

- Sweetpotato stem borer (Omphisa anastomosalis)

- White grub (Phyllophaga ephilida)

- Sweetpotato butterfly (Acraea acerata)

Market & Trade

- Recorded total export value of USD 56,263 in 2021 (Potatoes)

___

General Overview of Sweetpotato Production

Sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas L.) belongs to the morning-glory family. In spite of its name, it is not related to the potato. Unlike the potato which is a tuber or thickened stem, the sweetpotato is a storage root. Despite a physical similarity, yams are not related either.

Sweetpotato is currently ranked as the seventh most important crop in the world with a total production of 89,487,835 tonnes in 2020 (FAOSTAT, 2020). Asia accounts for close to 76% of world production, followed by the African continent (19.5%). The top five producers are China, Malawi, Nigeria, Uganda, and the United Republic of Tanzania (FAOSTAT, 2019). Though its origins lie in Latin America, Asia is now the largest sweetpotato-producing region in the world, with figures showing over 90 million tons produced annually. China is the world’s biggest producer and consumer of sweetpotato, where it is used for food, animal feed, and processing (as food, starch, and other products). China is the highest producer with production figures around 75.6 million tonnes, followed by Tanzania and Nigeria that produce up to 3.57 and 2.73 million tonnes, respectively. Sweetpotato is among five most important crops in 40 developing countries beside rice, wheat, maize, and cassava (A. Elameen et al, 2008).

Sweetpotato is increasingly becoming a vital crop in the Ghanaian economy for addressing food security issues and a source of income for various actors in the commodity value chain. It is the third most important root and tuber crop after cassava and yam. It is estimated to be cultivated on about 28,798,180 hectares of land in sub–Saharan Africa (FAOSTAT, 2020).

In Ghana, the crop is widely cultivated in the Northern, Upper East, Upper West, Central, and Volta Regions by smallholder farmers (J. K. Bidzakin, K. Acheremu, and E. Carey, 2014). According to Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) of the United Nations, Ghana recorded sweetpotato production of 135,000 tons in 2013 and this was the highest output recorded in the last fifteen years.

Sweetpotato production is increasing in Ghana and has become a major source of livelihood in production areas. Sweetpotato comes in varieties with skin and flesh color that range from white to yellow, orange, and deep purple. Orange-fleshed sweetpotato (OFSP) is an important source of beta-carotene, the precursor to Vitamin A. The crop generally is a rich source of vitamins (A, B-1, 5, 6, niacin, riboflavin), minerals (iron, calcium, magnesium, manganese, and potassium) and dietary fibre that are essential for good health.

Other attributes about the sweetpotato crop is the fact that, it is able to provide a good cover for the soil surface to control weeds, conserve soil moisture, minimize soil erosion and increase soil organic matter. It is hardy and can do well under marginal soil conditions.

Over the last two decades or more, sweetpotato has gained prominence due its short growth cycle and ability to survive in diverse agroecology and water stress soils (D. Markos and G. Loha, 2016). These traits project sweetpotato high among resource-poor farmers as yields of 15 to 30 t/ha can be obtained with minimum use of external inputs. Research evidence suggests that orange-fleshed sweetpotato (OFSP), in particular, could play a role in combating vitamin A deficiency among children and women in Africa and parts of Asia (J. W. Low et al, 2007).

Currently, there are 21 high yielding improved varieties developed by the research institutes mainly CSIR-Crops Research Institute and CSIR-Savanna Agricultural Research Institute, with different uses including, flour, juice, starch etc. However, these are insufficient to meet the different needs and the growing demand for improved varieties to satisfy the emerging markets. Hence the need to develop and disseminate more superior varieties.

Hitherto, the vast majority of varieties were low yielding white-fleshed cultivars which have low or no beta-carotene. However, the Root and Tuber Improvement and Marketing Programme (RTIMP), West Africa Agricultural Productivity Programme (WAAPP) and other partners have made tremendous strides at introducing OFSP and other high yielding cultivars particularly with resistance to the sweetpotato virus disease. This has helped in increasing the production levels.

However, widespread production and utilization challenges such as poor access to vines, and field pests and diseases as well as postharvest storage, preservations, and utilization issues still exist (P. E. Abidin, J. Kazembe, R. A. Atuna et al., 2016). Shortage of seed at planting time is still a chronic challenge across West Africa. During field production, a complex of biotic constraints, including nematodes, viral diseases, soil arthropods, weevils, and foliage feeding insects have been reported (H. Muyinza et al,. 2012). Overall, the African sweetpotato weevils (Cylas brunneus F. and C. puncticollis Boheman) pose the most threat, followed by the sweetpotato butterfly (Acraea acerata Hew.) and the clearwing moth (Synanthedon spp.) (J. S. Okonya and J. Kroschel, 2013). Preserving the fresh produce shelf-life remains a major challenge to farmers, traders, and consumers across sub-Saharan Africa (E. Mutandwa and C. T. Gadzirayi, 2007). High losses in quantity and quality are recorded as farmers and traders lack the capacity to use cold chain facilities to reduce physiological and microbial breakdown. This leads to seasonal glut and low prices which affect the economic returns to actors. Another constraint is the low patronage compared to other root crops which is attributed to lack of end-user preferred cultivars that allow for daily consumption as a staple (E. Baafi et al., 2015).

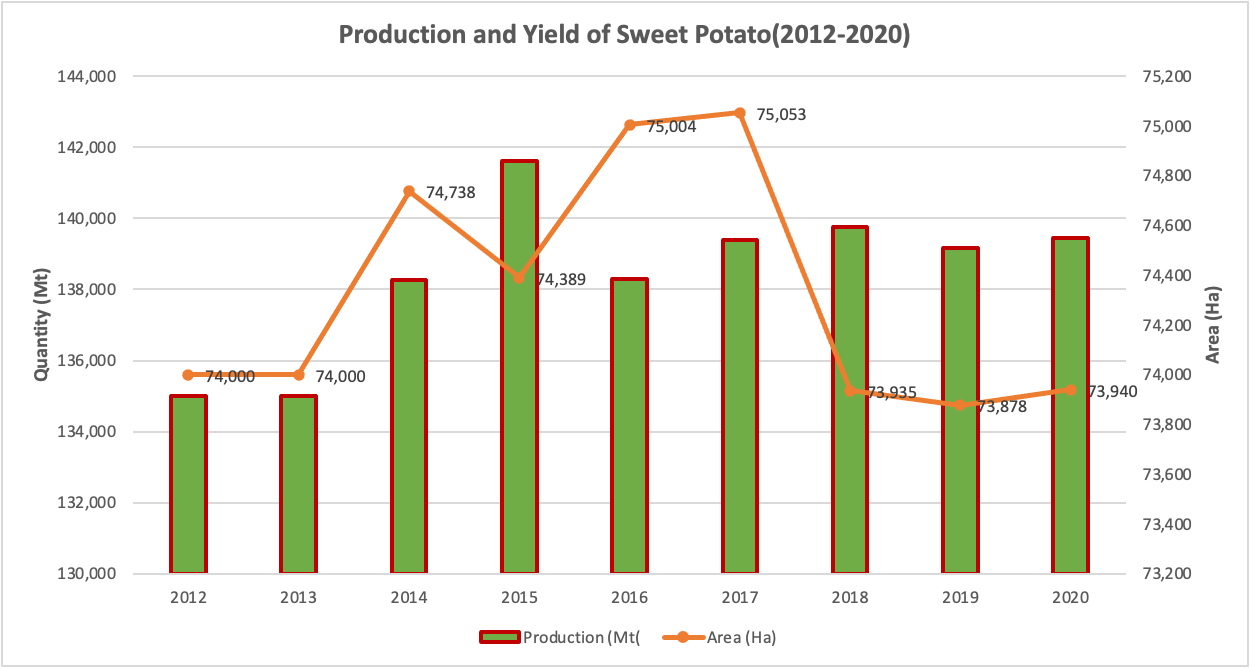

Between the years 2009 and 2019, sweet potato has seen a marginal growth in production even though there are efforts to intensify its cultivation. Figure 1 shows a trend in the area put under the cultivation and production of sweet potato between the years 2012 and 2020. According to FAOSTAT, the estimated area cultivated for as at 2020 was 73,940 ha. The estimated sweet potato production for the same year stood at 139,439 MT.

Figure1: Production and Area cultivated under Sweet potato in Ghana between 2012and 2020

FAOSTAT, 2019

Value Chain mapping and Key Actors

The sweetpotato value chain like any other value chain is one operated by various actors. These actors have their specific roles they play in order to attain an effective value chain performance. The numerous activities that are undertaken to produce various commodities and make them readily available for consumers are applied in the concept of value chain. These systems encompass actors and organizations, functions and products, cash and value

that make possible the transfer of goods and services from the producer to the final consumer.

According to Bezabah and Nugussie (2011) the major processes involved in the sweetpotato value chain comprises of input supply, technical support (extension service), production, processing, trading and consumption. At every stage of the chain, some form of cost is incurred, transactions take place and generally some form of value is added.

The sweetpotato value chain in Ghana comprises a range of stakeholders, including producers/farmers, aggregators, processors, exporters and transporters, as well as companies that provide support services (figure 3). The value chain analysis focuses on the different stakeholders at each operational level in the sector. It is not as well developed like the other roots and tuber crops like cassava and yam. The number of farmers or percentage of farmers in Ghana engaged in its production is yet to be established. There also seem to be mistrust among the local farmers because most of the farmers have different opinions on how the product should be marketed.

There are five groups of people that help get the sweetpotato to the market. They include, the farmers, traders, commission agents, processors and final the consumers. They all deal with each other in a private and individual basis. Transportation of the sweetpotato is mostly done by outside source such as hired transport (pick-up trucks, tricycles or hand-pushed trucks etc).

The sweetpotato value chain is also supported by a number of service providers, such as agro-input and agronomic support institutions, which provide training, planting materials, agrochemicals and other forms of agronomic support. Other key stakeholders with vertical links to the chain include processing equipment manufacturers and financial institutions.

Input Provision

In the production areas of Ghana, it is noted that sweetpotato farming or production system is characterized by traditional and insufficient farming inputs. Very few producers use improved planting materials, apply agro-chemicals, fertilizers, storage facilities; etc thus, contributing towards the low yield and poor shelf-life of sweetpotato roots (Verter and Becvarova, 2015). For instance, it is revealed that most farmers in Ghana, do not use inorganic fertilizers in cultivating sweetpotato. The reason behind the low use of fertilizers is the perception that fertilizers have adverse effects on food quality and storability (Mignouna, et al., 2014). This limited use of improved technology and innovation in sweetpotato value chains has been confirmed (TRAVERASURVEY, 2018).

As a practice, agro-input dealers basically perform the function of procuring agricultural inputs for onward sales to farmers to ensure the physical production of the crop. Main inputs supplied by these dealers for sweetpotato production include chemicals (herbicides, pesticides) and farm tools. However, most input dealers provide technical support to farmers in the form of appropriate chemical recommendation and proper agro-input usage based on instructions since most farmers can hardly read prescriptions on labels for appropriate usage.

Healthy planting material is the basis for a good sweetpotato crop. Sweetpotato is usually planted using vine cuttings. Most farmers retain part of their (smaller) roots or harvest part of their vines as seed material for the following cropping season. There is generally inadequate seed or planting materials because of insufficient multiplication and as a result, farmers use their seeds for a larger number of cycles. The practice affect productivity over time.

Production

In Ghana, sweetpotato is cultivated by smallholder farmers with average farm size between 0.04 and 0.4ha. It is mainly cultivated in the Guinea, Coastal and Forest-transition ecological zones. Major Regions of cultivation include Central, Greater Accra, Volta, Eastern and Upper East. Sweetpotato is usually produced under either mono-cropping or intercropping system. It can be intercropped with maize, plantain and cassava and as well rotational with legumes and cereals.

Land preparation for sweetpotato cultivation consists of bush burning or tractor ploughing after which hoes and sometimes mattocks are used to prepare mounds. Ridges are sometimes made with hoes and in certain cases on ploughed land. Different production practices are adopted by farmers in the various sweetpotato growing areas. Farmers especially in the Upper East region construct ridges using bullock ploughs. In the Central and Volta Regions of the country, sweetpotatoes are planted predominantly on irregularly and widely spaced mounds resulting in low plant populations. The crop is mostly planted directly on the flat ground without mounds or ridges. It is however highly recommended that farmers cultivate the crop on either ridges or mounds for easy maintenance practices and higher crop yields.

Yields are relatively low, with some estimates as low as 5-10 MT/ha though the potential is about 30 MT/ha and more for improved varieties. The low yields can be attributed to extensive use of unimproved landraces, pests and diseases attacks and poor agronomic practices adopted by farmers.

According to FAOSTAT, 2018, the estimated area cultivated for sweetpotato in Ghana was 73608ha. The estimated production also stood at 150,926 MT the same year. The current production estimate is expected to increase due to recent research and extension interventions in sweetpotato production in Ghana.

Major constraints in sweetpotato production in southern Ghana (Brong Ahafo, Ashanti, Eastern, Greater Accra, Central and Volta Regions) are low plant population density due to widely spaced mounds, variable planting dates, no organic or inorganic fertilizer application, and lack of market in the Ashanti and Brong-Ahafo Regions (Dankyi et al., 1997; and Anchirina et al., 1997) and non-availability of planting material.

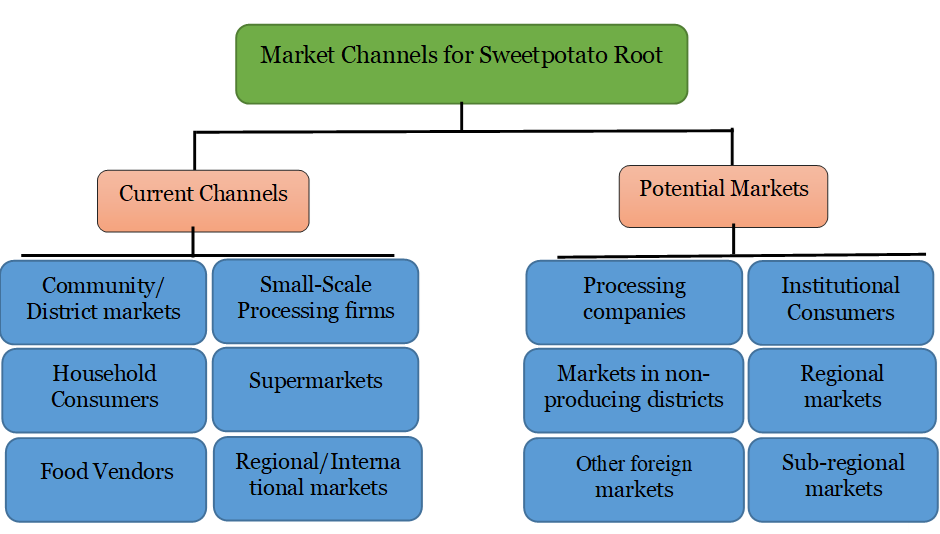

Trade

The current market participants consist of farmers, traders (including exporters), processors, and consumers. The players are mainly smallholders operating privately on individual basis. The industry is largely a fresh produce market, targeting food vendors, supermarkets, processors, the regional/international markets and direct selling to wholesalers, retailers, and household consumers (figure 4).

Figure 4: Market channels for Sweetpotato root

Sweetpotato farmers supply directly to traders (including exporters), either at farm gates or local markets. Traders in turn supply directly to local processors, consumers and some identified markets in the region and Europe after they have been sorted, graded and packaged for price determination. Middlemen who are also traders usually transport the produce by using hired trucks to districts or urban markets and neighbouring or bordering countries. Ghana export fresh roots to neighbouring countries such as Togo and Burkina Faso through middlemen. The choice of these markets is due to ready markets but not higher prices. From key informant interviews, the concerns of traders and processors were similar in that the main issues are related to the narrow period of harvesting and lack of storage methods to extend shelf-life of fresh produce, resulting in glut and low prices.

There is little regulation and standardization, and prices are determined by market forces of demand and supply.

As the industry grows and expands, it is anticipated that, other foreign markets will be identified for trade and commerce.

Processing

Sweetpotato processing in Ghana remains very basic, with smallholders accounting for the majority of processing for home consumption and the food market. White-fleshed cultivars have already been contributing to household food security, but orange-fleshed cultivars now have the potential to alleviate vitamin A deficiency when incorporated into familiar foods.

With high starch content, it is well suited to processing and has become an important source of raw material for starch and starch-derived industrial products. Added value for farmers comes from a variety of products and ingredients made from sweetpotato root including flour, dried chips, juice, bread, noodles, candy, and pectin. Industrial uses such as the production of starch, alcohol, and partial flour substitute are further utilization options that are being explored in Ghana. Several food forms and industrial products even take their roots from the crop. Many of these products have become exportable over the years as a result of advancements in processing technology and the increasing industrial attention.

Another option is sweetpotato fodder and silage for livestock feeding, which has high protein and digestibility values. New products include liquors and a growing interest in the use of the anthocyanin pigments in the purple varieties for food colourings and use in the cosmetics industry.

A few largescale industrial companies are emerging as important value chain players. Example is the Casa de Ropa Company in the Central Region. This company is dedicated to producing high quality orange-fleshed sweetpotatoes (OFSP) by organic cultivation, operating modern equipment for processing, maintaining a work environment that meets international food standards. They are also specialized in the production of value-added agricultural products (flour for food products and household meals).

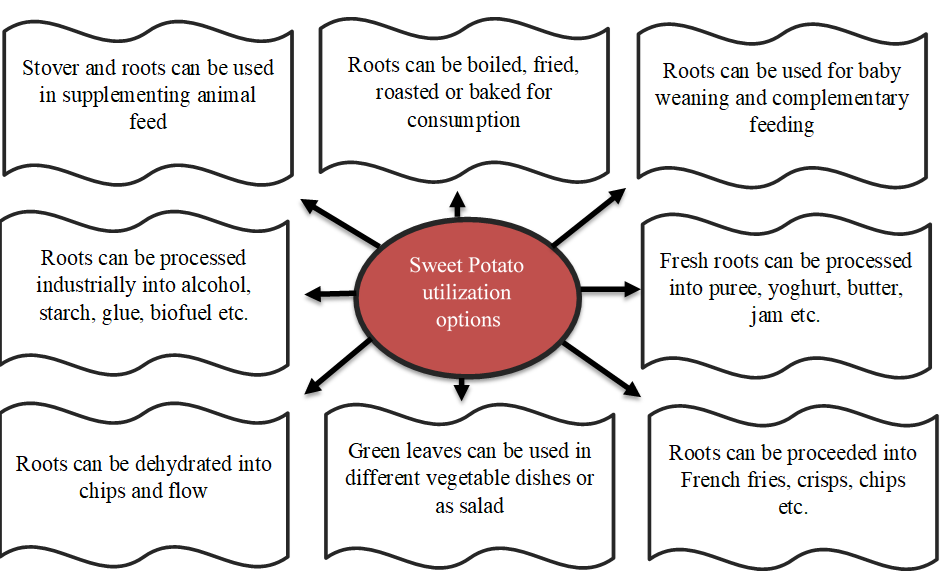

Consumption (Utilization of Sweetpotato)

Many parts of the sweetpotato plant are edible, including the root, leaves, and shoots. Sweetpotato vines also provide the basis for a high-protein animal feed. Although the leaves are edible, the starchy storage roots are considered the most important product. The roots are mostly boiled, fried, roasted, or baked for their rich source of dietary energy and quite recently for their beta-carotene and vitamin C. The roots can also be processed industrially into alcohol, starch, glue, biofuel etc. (figure 5).

Figure 5: Options for Sweetpotato utilization

Key Agronomic Practices and their Importance

Good Agricultural/Husbandry Practice

| Brief Description and importance |

|---|---|

Planting Material/ Variety Selection

| The basic planting material used for cultivation is vine cuttings. They may also be propagated by the seed (small tubers). Plant varieties that are preferred by consumers; grow fast, give good yields and tolerant to major diseases and pests. Most improved varieties respond to these attributes. Some improved varieties include Sauti, Santom pona, Okumkom, Faara, Apomuden, Otoo, CRI-Ligri, CRI-Patron, AGRA-SP 09, SARI-Nan, CRI-Gavana etc. Select varieties that would meet the demand or consumers preference. Selection of a variety should also be based on weather information and preferred agro-ecology. Always purchase or acquire cuttings from certified seed producers where viability and variety purity can be guaranteed. Healthy planting material is the basis for a good sweetpotato crop.

|

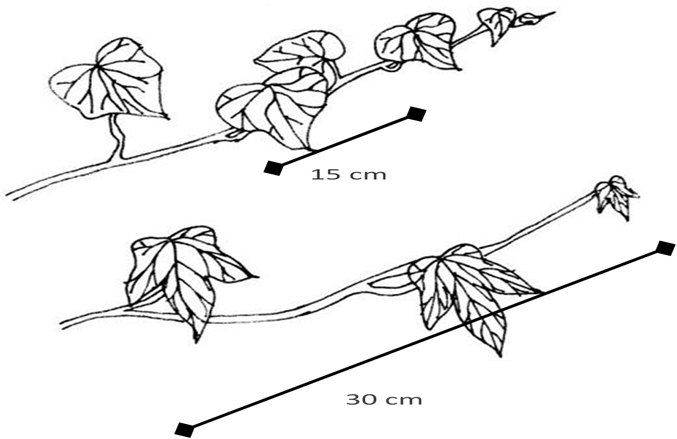

Planting Material Production

| To produce your own vines for planting, raise a nursery near a source of water or plant in wet inland valley during the dry season. Prepare vine cuttings as follows:

Note:

|

Choose suitable soils

| Sweetpotato can be grown on many types of soil but does best on deep, moderately fertile, sandy loam soils, which produce high quality storage roots with an attractive shape and appearance.

Adequate drainage and soil aeration are important, which is one of the reasons the crop is usually grown on mounds, ridges or beds. The pH of the soil is also important as it affects the availability of the nutrients in the soil to the plant. Sweetpotato does best on slightly acid soils, with optimal pH 5.6‐6.6, but can tolerate soils with higher and lower pH. If the soil’s pH is more acidic (e.g. <5) then agricultural lime should be incorporated into the soil before planting Sweetpotato, like other crops, obviously benefits from good soil fertility. As a root crop, sweetpotato has a high requirement for potassium. However, a high soil nitrogen content may lead to excess foliage growth and limited root production, particularly in humid environments. Farmers rarely add fertiliser to their sweetpotato crop, but the crop benefits from residual fertility when it follows or is intercropped with a fertilised crop such as maize.

|

Agro Climate Conditions

| Sweetpotato thrives when cultivated in the Guinea, Coastal and Forest - transition ecological zones. For maximum yields and production of a good quality crop, cultivate sweetpotato in an ecology with an annual rainfall of between 750 and 1,000 mm during the growing season.

The crop is especially sensitive to drought at establishment and from 20 to 30 days after planting when the storage roots start to develop.

|

| Land Preparation | Good land preparation enhances sprouting, crop establishment and reduces competition with weeds. Land preparation for planting is the single most labour‐intensive part of sweetpotato production. The following methods of land preparation may be used:

Follow any of these options:

During land preparation, the mounds, beds or ridges may be constructed by heaping soil up and over the residues of previous crops or vegetation from fallow periods. This is to provide fertility for the sweetpotato crop and to loosen any compressed soil that might hinder root formation. Farmyard manure, compost, or green manures can be very beneficial, if available, but may be more likely to be applied in a kitchen/ backyard garden setting than in a large production field. Ash is rich in potassium and can be incorporated into soils to help boost sweetpotato root formation.

|

Planting

| Sweetpotato is planted on mounds, ridges or flat beds. Good soil aeration is needed for storage root initiation and growth. Thus, for higher yields, the height of the mound or ridge is important. Mounds and ridges ensure good drainage and make it easier to harvest the matured roots, especially when harvesting is done in a piecemeal fashion as is often the case with sweetpotato. Whether mounds or ridges or beds are used, their sizes vary among locations; usually based on what is most practical for farmers in that area. Where tractors or ox‐ploughs are available, ridges are typically preferred, but ridges, mounds and beds can all be prepared manually. In households where there are labour shortages, sweetpotato may be planted in flat beds. This results in lower yields than when ridges or mounds are used. Sweetpotato vine cuttings or sprouts, at least 3 nodes (about 20‐30 cm long are usually planted at a spacing of 25‐30 cm between plants and 60‐100 cm between ridges, although farmers like to experiment with different spacings and will usually plant varieties with trailing vines wider apart than those with semi‐erect or erect vines. Where sweetpotato is grown on mounds, farmers usually plant 3 vines per mound with some space between the vines. At a spacing of 1 m x 1 m between mounds, 30,000 cuttings are required per hectare if 3 cuttings per mound are used. While on ridges 33,333 cuttings are required to plant a hectare at a spacing of 30 cm between plants and 1 m between ridges. Adjustment of spacing can be used to control storage root size, with closer spacing producing a greater proportion of smaller sweetpotato roots, which are preferred by some markets. To plant, a stick, machete or hoe is used to make a hole that most of the cutting (at least two nodes should be under the soil to enhance establishment and increase the number of roots that form) is placed into the soil, leaving only the tip exposed. The soil is firmed into place to ensure good contact between nodes and the soil. Sometimes lower leaves are removed before planting, but this is not necessary. Farmers sometimes hold cuttings for a day or two in a cool, shady place to encourage root initiation prior to planting. In many places farmers traditionally use two vine cuttings per planting hole, however this requires a lot of extra planting materials, and extensionists recommend using just one cutting per hole and then gap filling any plants that fail to establish. On mounds, the three cuttings are planted towards the top of the mound but equidistant from each other in a triangle configuration. On ridges, the cuttings are planted either vertically or at a slant along the top of the ridge at the required spacing. Sweetpotato is often planted after the priority cereal crops and other important cash crops, and when sufficient planting materials have been generated by the rains. However, in areas with a short rainy season these delays in planting can end up exposing the sweetpotato crop to drought periods and weevil damage, significantly reducing potential yields.  |

Pest and Disease Management

| Major pests of sweetpotato in Ghana are the Sweetpotato Weevil (Cylas sp.), Striped Sweetpotato Weevil (Alcidodes sp.) and Sweetpotato Butterfly (Acraea acerata). These pests can cause considerable damage to sweetpotato and therefore reduce crop productivity. They must therefore be effectively managed through an integrated approach to optimize crop yield. Integrated Pest Management This involves the utilization of a variety of methods and techniques including: Cultural, Biological and Chemical. It is based on prevention, monitoring and control. The best way to control pests is to grow a healthy crop. The use of tolerant varieties, clean planting materials to reduce pest population, practicing crop rotation and earthing up ridges during weeding helps to control pests. Use recommended chemicals to control insect pests when their population reaches economic threshold. Consult the agricultural extension agent for technical advice on the type of insecticide to use. Sweetpotato Virus Complex (SPVC) is the major disease attacking sweetpotato. Infected plants are stunted with shrivelled and chlorotic leaves. The following are recommended practices for effective disease control

|

Soil Fertility Management

| All crops absorb nutrients from the soil, and when the crop is harvested these nutrients are removed from the soil. In order to maintain the nutrient levels of the soil, nutrients must be returned to the soil. This can be partially done through ploughing crop residues back into the soil and letting the plant materials decompose and return their nutrients to the soil, or by adding fertilizers (which can be in the form of organic manures and composts or chemical fertilizers). In Asia, sweetpotato vines are typically used as green manure. Plants need nutrients not only for their growth, but also to enhance their resistance against diseases.

Sweetpotato, as with most root crops, absorbs more potassium (K) but less nitrogen (N) and phosphorous (P) than maize does. Potassium is the most important element for storage root development, and so in many places sweetpotato will benefit from extra potassium. This can be provided using ash, as ash is rich in potassium. However, it is not only the amount of potassium that is important, but also the ratio between the potassium and nitrogen to be supplied. The best bulking of storage roots occurs when the nitrogen and potassium are present in the soil at a ratio of about 1:3. Applying potassium during the second half of the crop’s growth cycle helps promote development of a strong skin.

Nitrogen (N) if present in too high concentrations can result in abundant vine growth but poor root development. This is particularly damaging if nitrogen is applied after the middle of the crop’s growth period. Although sweetpotato does well even on very poor soils, if nitrogen levels are too low the plants have limited vine growth and low yields.

Nutrients can be added to the soil in several ways. Farm yard manure can be used and is often more readily available than synthetic fertilizer. As the nutrient content of all manures differ it is difficult to recommend application rates, and it is more sensible for farmers to experiment with a range of different application rates to see which produces the best crop on their field. Manure needs to be added a few weeks in advance of the crop being planted to ensure that it has time to partially decompose before the crop is planted. Undecomposed manure introduces weeds to a field and should be avoided.

General recommendation

Agroecological zone

NPK Recommendation (N-P2O5-K2O)

Recommended Blend (N-P2O5-K2O)

6 bags per hectare (apply as split; 4 weeks after planting and 16 weeks after planting – all spot placement) OR Apply 3-4 bags per hectare or 20g of fertilizer per plant at 4 weeks after planting and 1.5 bags of urea and 1 bag of Muriate of potash mixed as second application at 16 weeks after planting – spot placement and covered. However, as all soils differ it is best to experiment with different rates in your field or get a soil analysis done to obtain the fertilizer rate to apply. The most efficient way of applying fertilizer (whether organic manures or industrial chemicals), is to side dress in a furrow, applying and incorporating the required amount for each plant. |

Weed Management

| Weeds compete directly with plants and reduces yield. Practice of managing weeds that damage agricultural crops is very essential. Such measures include, targeted use of recommended agrochemicals, altering the planting dates and good agronomic practices and cropping system etc. NB: The use of weather information and early warning systems guides farmers on the choice of appropriate crop protection measures to adopt against weeds. Weed competition reduces canopy development and root bulking causing yield loss. Weeds also reduces the quality of planting materials, harbor pests and diseases, obstructs farming activities etc. The following weed control measures are recommended:

Weed control is most successful when it involves an integrated approach using a variety of methods. |

Sweetpotato Cropping Systems

| Mono-cropping Sweetpotato is commonly grown under sole cropping by small to medium scale farmers Sole cropping is advantageous because the correct plant population per unit area is achievable. In addition, it is easier to mechanize field operations in sole cropping systems.

This makes sole cropping more compatible with large-scale production systems. Cultural practices such as, weed control and pesticide application are much easier in mono-cropping system. However, in the event of an outbreak of diseases and insect pests, total crop loss may occur. Intercropping In some areas sweetpotato is intercropped with other crops. This occurs particularly in areas where land pressure is high or labour for constructing ridges is limited. Intercropping, in addition to improving crop and food diversity, can also: improve labour efficiency, increase soil fertility if nitrogen fixing intercrops are used and reduce weed growth. Intercropping of sweetpotato is easier when it is grown on ridges. As with all intercropping, the cropping pattern should try and minimise the competition for light and nutrients between the two or more crops being intercropped. If intercropping sweetpotato with beans, soybeans or peas, sweetpotato can be planted along the ridge and a row of beans on either side of the ridge.

Advantages of Intercropping include

Crop rotation Sweetpotato can be cultivated in rotation with other crops. E.g: legumes and cereals. Sweetpotato following three seasons of cowpea has been found to give good yields. Advantages of crop rotation include:

|

Harvest Management

| Harvest early or at the right time to avoid field losses. Timely harvesting and post-harvest operations in sweetpotato is very important to maximize yields, minimize postharvest losses and quality deterioration.

The optimum time of harvest depends on the variety’s maturity period. It may be harvested over a period of time. However, sweetpotato may be harvested in piecemeal (staggered) or once (whole field harvest). The period of harvest may be influenced by some of the following factors:

Note: Farmers are to consider the merits of these factors in relation to the potential and needs of their farm enterprise.

Harvesting of sweetpotato is done manually with hoes and cutlasses. Harvest by removing the vines from the ridge or mound and carefully dig-out the roots from the soil.

Avoid root injuries which could lead to deterioration. |

Post-Harvest practices

| Processing and Storage

Sort harvested roots based on size, undamaged or damaged before transporting from the field. Thebulky nature and short-shelf life of fresh roots after harvest presents a lot of post-harvest handling challenges. There are various storage techniques (fresh or dry storage) to minimize loss of harvested roots. The method for fresh roots storage includes:

Note:

Curing Basically, when you cure a potato, you put the potato through a process that takes all those starches and breaks them down into natural sugar. This is what gives a sweet potato their naturally sweet flavor. Sweetpotatoes must be cured after harvest before they are stored. After digging, allow the roots to dry for two to three hours. Don't leave them out overnight where cooler temperatures and moisture can damage them. Once the surface is dry, move them to a warm, dry, and well-ventilated place for 10 to 14 days. To cure roots of sweetpotato, hold them at about 30oC (85 degrees F) with 90 to 95 percent relative humidity (RH) for 4 to 7 days. After curing, reduce the storage temperature to about 12-16oC (55 to 60 degrees F) at 80 to 85 percent RH. Most properly cured sweet potato cultivars will keep for 4 to 7 months. Packaging and Transportation Potatoes are mainly transported in wide-meshed bags, but are sometimes also transported in perforated plastic bags, crates, cartons and baskets. Sweetpotatoes are usually marketed in bulk; in the superstores they are usually pre-packaged in plastic trays covered with plastic.

|

Export Markets (Existing and Potential)

Export Markets (Existing and Potential)

According to the Ghana Export Promotion Authority (GEPA) 2020 report, Ghana’s export of sweetpotatoes saw a positive growth rates of 23.3% in 2019, recording a total export value of USD 434,000 as compared to 2018 earnings of USD 333,000. With 9 market destinations, Ghana had a global market share of 0.1% at a rank of 40. The top 4 global leading exporters of sweetpotatoes are USA (USD 188M), The Netherlands (USD 162M), Spain (USD 53M) and Egypt (USD 48.4M). Although Ghana has witnessed growth of its export of sweetpotatoes for the past 5years, its exports are still insignificant on the global scale. France and Italy were the top two (2) largest export destinations for Ghana, with import value of USD 138,000 and USD 129,000 respectively, constituting 61% market share of Ghana’s export of sweetpotatoes. Other importers of sweetpotato from Ghana were Belgium (USD 81,000), Canada (USD 65,000) and UK (USD 18,000).

Between 2018 and 2019, France, Italy and Belgium showed the highest growth rates under import of sweetpotatoes from Ghana by 2522%, 597% and 294% respectively. Ghana saw a decline in its annual growth rate to the Netherlands, and Canada by -98%, and -14% respectively in 2019. In addition, UK, Norway and Canada had a negative average annual growth of -36%, -21% and -9% respectively from 2015 to 2019.

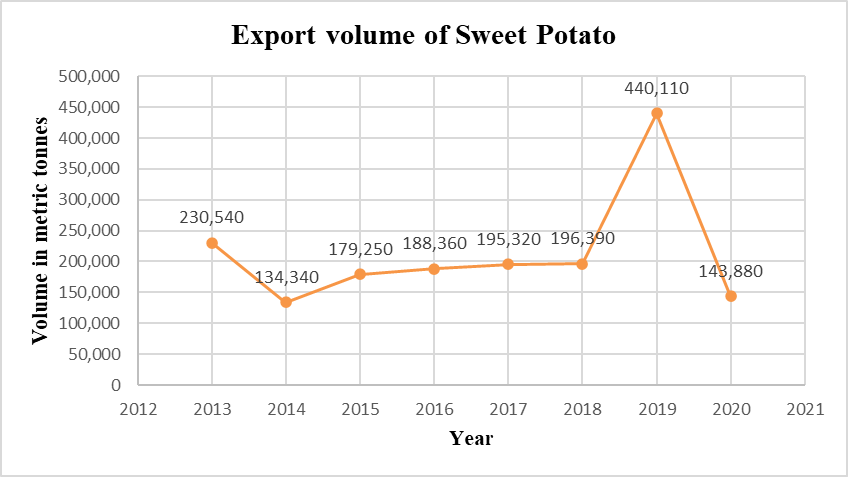

Tridge, a renowned consulting firm revealed that the export volume of Ghana’s sweetpotato to its major market destinations was 143,880 MT in 2020. This figure was a sharp drop in volume the preceding year (2019) which was 440,110 MT (figure 6).

Ghana’s export of sweetpotatoes to its market destinations is considerably very low given that these markets are seen as the top ten (10) largest global importers of the commodity. The Netherland (USD 151.2m), UK (USD 120.2M), Canada (USD 65m), Germany (USD 64m), France (USD 53.3m), Belgium (USD 37m), Thailand (USD 23m), Hong Kong China (USD16.4m), Japan (USD16.1m) and Singapore (USD 15m), had the biggest demand for sweetpotato in 2020. In 2019, Italy was at 7th position with import value of USD10m.

The Global demand for sweetpotatoes was valued at $739,247,000 with a registered growth rate in value of 7% in 2019-2020 against 23% in 2018-2019. The Netherland was the biggest importer of sweetpotatoes at a value of USD151,211,000 in 2020 against USD 157,096,000 in 2019 with a market share of 20.5% and 22.5% respectively. Other notable global importers with notable growth rates were UK, Canada, Germany, France and Belgium.

According to GEPA’s report, new and potential market with significant average growth rates, favourable tariff regimes and favourable geographical distance to be explored for market diversification and penetration for Ghana's export are Spain, Switzerland and Norway. Import tariffs of European countries applied on Ghana is 0%, which is comparable to the leading suppliers to the EU (table 1).

Table 1: - Selected Potential new markets for Ghana (based on import value above $5,000,000)

| Markets | Imports 2018 US$ | Average Annual Growth 2015-2019 | Tariff | Ghana’s Share (%) | Leading Suppliers |

Spain | 7,308,000 | 54 | 0 | 0 | USA (22.8%) Netherlands (14.4%) |

Switzerland | 6,985,000 | 17 | 0 | 0 | USA (43.6%), Spain (24%) |

Norway | 7,425,000 | 4 | 0 | 0 | USA (58%) Spain (19.8%) |

GEPA, ITC Trade map 2020

Figure 6: Export volume of Sweetpotato (2013-2020)

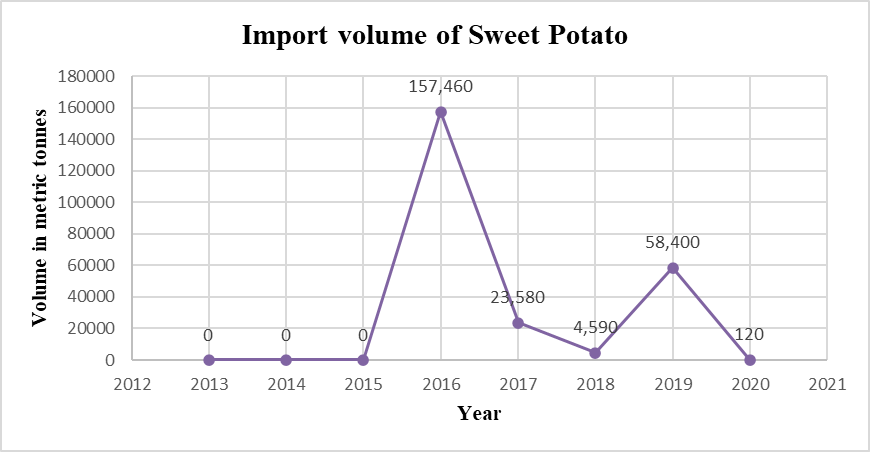

Figure 7: Import volume of Sweetpotato (2013-2020)

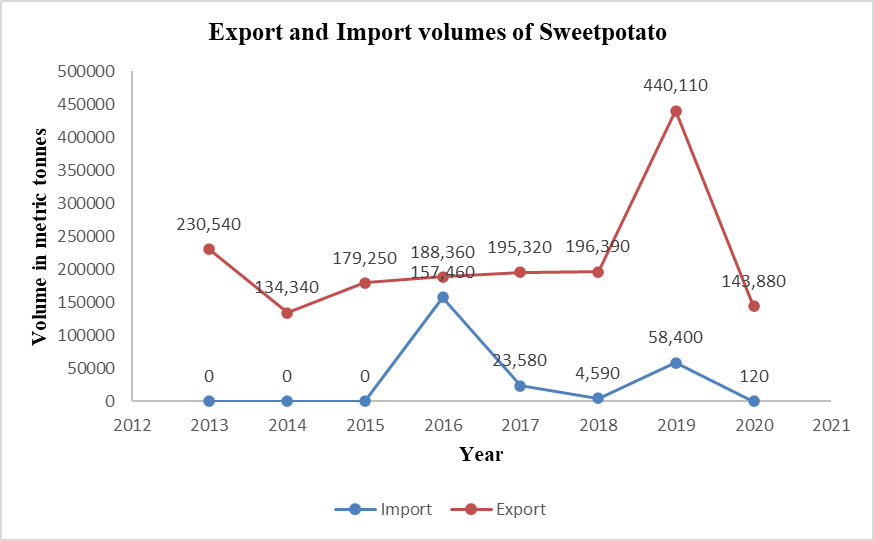

Figure 8: Export against Import volume of Sweetpotato (2013-2020)

Even though Ghana is exporting to the international market sweetpotatoes being produced in-country, the country still imports some quantities to make up for the shortage in requirements. The country’s import in respect of the commodity since the past five years is reducing (figure 8).

General Export Requirements

Europe imported 244,000 tonnes of sweetpotatoes in 2017, compared to 96,000 in 2013. Sweetpotatoes have gained much popularity because of a strong promotion in Europe. The United States of America is the leading supplier, and this shows in the fast growing import figures in Europe. The import from developing countries is however increasing steadily, but still far behind the dominant supply from the United States.

The attention for ethnic food and healthy nutrition have also contributed to the popularity of sweetpotatoes. They have become so popular in the United Kingdom.

Pesticides maximum residue levels

Regarding trade of sweetpotatoes in the European market, pesticide residues are one of the crucial issues for suppliers. To avoid health and environmental damage, the European Union has set maximum residue levels (MRLs) for pesticides in and on food products. Products containing more pesticides than allowed will be withdrawn from the European market.

Note that buyers in the United Kingdom and several Member States such as Germany, the Netherlands and Austria, use MRLs which are stricter than the MRLs laid down in European legislation. Supermarket chains are the strictest and manage 33 to 70% of the legal MRL.

Quality

There are no official quality requirements. Therefore, the minimum requirements of the General Marketing Standards of Regulation (EU) 543/2011 apply. The general marketing standards state that products shall be:

- intact and sound;

- clean, practically free of any visible foreign matter;

- practically free from pests;

- practically free from damage caused by pests affecting the flesh;

- free of abnormal external moisture;

- free of any foreign smell and/or taste.

The condition of the products must be such as to enable them:

- to withstand transport and handling;

- to arrive in satisfactory condition at the place of destination.

Conformity checks are also part of European Regulation (EC) No. 1580/2007. In the event of non-compliance your product can be rejected. In certain third countries like Ghana, local inspection bodies carry out pre-export checks.

Packaging

Packaging requirements for sweetpotatoes differ between customers and market segments. They must at least be packed to protect the produce properly, in new, clean and quality packaging material to prevent damage to the product.

- For wholesale, sweetpotatoes are packaged in cardboard boxes or crates. These boxes can vary in size. Six (6) or ten (10) kilogram boxes are often used.

- In European retail outlets, sweetpotatoes are usually sold out of the wholesale box or in plastic crates. More recently, sweetpotatoes have become available in consumer packing (sealed plastic).

Labelling

Food placed on the European market must meet the legislation on food labelling. On the label or marking of each box should at least be the following information:

- Name and physical address of the packer and/or dispatcher;

- Product name;

- Country of origin;

- Commercial specifications: Class, size and weight;

- Traceability code (for example Global Location Number);

- Officially recognised code mark such as a GlobalGAP Number (GGN) (recommendable);

The name and address of the packer or dispatcher can be replaced by an official control mark.

For pre-packages you must also:

- Include the name and the address of a seller established within the European Union with the mention ‘Packed for:’ or an equivalent mention.

- Use a language that is understandable by the consumers of the country of destination.

For organic produce you must include the European organic logo and the code number of the control authorities.

Social and environmental compliance

There is growing attention in Europe for the social and environmental conditions in producing areas. Most European buyers have a social code of conduct which they expect suppliers to adhere to. Social compliance is important, although product quality has top priority.

A growing niche market for organic Sweetpotatoes

An increasing number of consumers prefer food products that are produced and processed by natural methods. The market for organic sweetpotatoes is still small, but with a growing demand and limited supply.

To market organic products in Europe, you must use organic production methods according to EU legislation. Furthermore, you must use these production methods for at least two years before you can market the vegetables as organic.

In addition, you (or your importer) must apply for an import authorisation from organic control bodies. After being audited by an accredited certifier, you may put the EU organic logo on your products, as well as the logo of the standard holder, such as the Soil Association (especially relevant in the United Kingdom), Naturland (Germany) or BioSuisse (Switzerland). Some of these standards differ slightly, but they all comply with the European legislation on organic production and labelling.

For further market information and market potential the click link : https://www.cbi.eu/market-information/fresh-fruit-vegetables/sweet-potatoes-0/market-potential

Price Trends

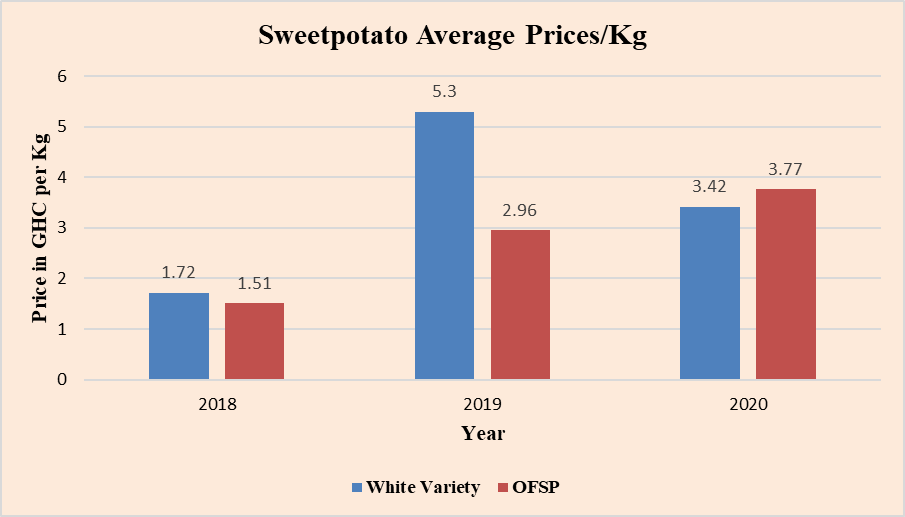

The Ghana National average wholesale market price per kilo for sweetpotato as at December, 2020 was GHS 3.42 and 3.77 for the white and orange fleshed types respectively. Price trends seem not to be stable over the past 5 years (Figure below). There has been a steady increase in the price of commodity in the various trading markets across the country especially for 2019. This increment in prices according to experts and personal interviews with farmers could be attributed to the importance being placed on the commodity in respect of food and nutrition security.

Tridge Company Limited also in their independent assessment published that, the export market price of sweetpotatoes from Ghana per tonne for the years 2013, 2017, 2018 and 2019 were US$ 625.00, US$ 490.57, US$ 569.44 and US$ 333.33 respectively. In 2021, the approximate price range for Ghana Sweetpotatoes for the export market is between US$ 0.33 and US$ 0.57 per kilogram.

National Average Wholesale Price for Sweetpotato

Key Risks Along the Value Chain and Mitigation Measures

| Value Chain Actions | Key Risks and Challenges | Mitigation Measure |

|---|---|---|

Input Supply

| Limited availability and access to improved planting materials | - Establishment of multiplication sites at the MOFA agricultural Stations to increase base of improved breeder materials. - Train farmers and entrepreneur to engage in secondary and tertiary planting material multiplication. - Farmers to establish own sweetpotato vine nursery. - Source planting materials (vines) from approved vine multipliers certified by PPRSD. |

| Finance | Inadequate/Lack of access to financial support and facilities from the banks and financial institutions

| - Link stakeholders along the value chain to Financial Institutions. - Training value chain actors to develop bankable proposals/business plans. - Create strong linkages among actors to establish trust. - Farmers to produce to meet market demands. |

High interest rates

| - Provision of incentives - Interest-free subsidies from government - Value chain actors to minimise risk | |

| Production | Low yield | - Understanding of Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs) - Use of certified, cleaned and improved planting materials - Encourage the establishment of planting material multiplication - Support the development of more improved varieties to meet market demands. - Ensure that each vine cutting is more than 2 nodes. - Avoid cuttings beyond the middle portion of the vine (hardened portions) - Maintain good plant population per hectare - Appropriate use of irrigation. |

Pests and disease incidence (eg. sweetpotato weevil etc.)

| - Select and use disease tolerant varieties - Altering planting dates - Use of IPM technologies - Crop rotation | |

| Declining soil fertility | - Carryout soil testing - Use appropriate recommended plant and soil nutrition. - Practice crop-livestock farming system if possible | |

| Non-adoption of improved technologies /Good Agronomic Practices (GAPs) | - Extension education on GAPs - Carryout on-farm demonstrations and field days | |

| Unpredictable weather | - Irrigation - Use of weather alerts from GMet - Crop diversification - Adherence to best agronomic practices | |

| Marketing | Inability to satisfy demand from various market segments | - Government support required for crop intensification to increase scale of production and to satisfy varied end users - Diversification of product lines - Creation of strong linkages among actors especially producers and processors |

| Market access | - Meet the required certification standards for the various markets especially exports. | |

| Sudden changes in demand as well as output and input prices | - Crop diversification - Contract farming - Marketing of produce through different channels - Market intelligence | |

| Post-harvest handling | Poor storage facilities/high produce perishability

| - Carryout further research on the improvement of shelf life/ - Promote the processing of sweetpotato into other products - Grading and sorting - Establish strong linkages between producers, processors and industrial consumers |

Cyclical glut

| - Create strong linkages among actors especially producers and processors - Encourage staggering of planting | |

| Processing | Capital intensive for medium-large scale industrial processing.

| Government to subsidize machinery and major activities of medium-large scale processors |

Limited product varieties/value addition meeting consumer preference

| - Encourage product diversification - Empower women to be effective in the aggregation and processing along the chain | |

| Raw material (low quality and volume) | - Processors to establish own farms - Contract farming - Train producers to meet specific requirements | |

| Sudden change in demand and output price | - Contract farming - Marketing of produce through different channels | |

| Consumption | High demand and competition for commodity and related products

| - Develop more varieties and specific varieties for industry. - Government support required for crop intensification to increase scale of production |

Major Pests & Diseases

Common Sweetpotato Pests

The major pests of sweetpotato in Ghana and across Africa are the Sweetpotato weevil (Cylas sp.), Striped Sweetpotato weevil (Alcidodes sp.), Sweetpotato stem borer (Omphisa anastomosalis), White grub (Phyllophaga ephilida) and Sweetpotato butterfly (Acraea acerata).

Sweetpotato weevil (Cylas sp.)

Picture of sweetpotato root infested with weevils (Cylas sp.)

Adult weevils feed on leaves, the underground storage roots and the vines of sweetpotatoes. They prefer to feed on storage roots, but at the beginning of the growing season, when the plants have not yet produced storage roots, the adult weevils live on the stem and leaves. They lay eggs on vines and leaves, and the grubs will feed in the stem or the leaf and pupate inside the vines.

A symptom of infestation by sweetpotato weevils is yellowing, cracking and wilting of the vines, but a heavy infestation is usually necessary before this is apparent. Damage by weevils can be recognised by the holes in the vines or the tunnels in the storage roots when you pull them up from the soil. Attacked roots become spongy, brownish to blackish in appearance.

The following are recommended practices for effective pest control:

- Use tolerant varieties.

- Use clean planting materials to reduce pest population.

- Practice crop rotation.

- Earthing up ridges during weeding. This helps to control pests and protects exposed roots.

- Use recommended chemicals to control insect pests when their population reaches economic threshold. Consult the agricultural extension agent for technical advice on the type of insecticide to use.

Sweetpotato stem borer (Omphisa anastomosalis)

Larvae bores into the stem leading to the storage roots. Feeding in the crown region leads to wilting, yellowing and dying of plant. The borers can be easily identified by the presence of faecal matter on the soil surface and holes on the stem.

Management/Control

- Keep the field free from weeds especially Ipomoea spp.

- Fallow the land for few season if infestation is more.

- Use treated and insect free planting material.

- Use pheromone traps to monitor and control the insect

- Practice crop rotation

- Hilling-up is effective when the holes that provide the adults with an exit from the stem are covered with soil. Earwigs and ants may attack the larvae developing within sweetpotato vines.

White grub (Phyllophaga ephilida)

Grub feeds on underground parts including main stem and roots. They also feed on roots by making tunnels. The infected plant become wilted and die eventually. White grub are the larvae of scarab beetles commonly called as May and June beetles. The grubs are white in colour and appear C shape. They generally feed on soil, organic matter and plant materials.

Management/Control

- Deep ploughing to expose grub and pupa present in soil.

- Provide proper drainage to soil to avoid excess moisture.

- Follow crop rotation with soybean to reduce grub population.

- Application of biocontrol agents like Bacillus popilliae and B. lentimorbus bacteria kill the grubs.

Common Sweetpotato Diseases

There are a number of diseases that attack sweetpotatoes both on the field and in storage. They include the following:

- Alternaria leaf spot

- Leaf and stem blight

- Sweetpotato virus disease (SPVD)

- (Sweetpotato feathery mottle virus (SPFMV) and

- Sweetpotato chlorotic virus (SPCSV)

- Fusarium root and stem rot (Fusarium solani)

Alternaria leaf spot & Leaf and stem blight (Alternaria spp.)

Random scatter of dark brown lesions with concentric rings and yellow halo

This is a fungal disease caused by Alternaria Cucumerina. Brown lesions on leaves with concentric rings resembling a target. The lesions are usually restricted to the older leaves and may be surrounded by a yellow halo; small gray-black oval lesions with lighter centres may occur on stems and leaf petioles and occasionally on leaves. The stem and petiole lesions enlarge and often coalesce resulting in girdling of the stem. Defoliation may also occur.

Stem and leaf petiole blight is much more destructive than leaf spots.

Management/Control

- Destroy all sweetpotato crop residue immediately following harvest

- Plant resistant or tolerant sweetpotato varieties where available

- Plant only disease-free seed material.

- Treatment for Alternaria requires fungicide to be sprayed directly on infected plants, as well as improvements in sanitation

- Practice crop rotation to prevent future outbreaks.

- Organic gardeners are limited to sprays of copper fungicides, making control much more challenging.

Sweetpotato virus disease (SPVD) (Sweetpotato feathery mottle virus (SPFMV) and Sweetpotato chlorotic virus (SPCSV)

Sweetpotato virus disease is a disease complex caused by two viruses; sweetpotato chlorotic stunt virus (SPCSV) and sweetpotato feathery mottle virus (SPFMV). The symptoms are severe stunting of infected plants, distorted and chlorotic mottle or vein clearing of the leaves. It is confirmed that SPCSV enhances the accumulation of SPFMV. The symptoms caused by SPCSV alone is negligible whereas symptoms caused by SPFMV is localized, mild and often asymptomatic and won't cause significant damage to the plant. Common symptoms include appearance of feathery, purple patterns on the leaves.

It is estimated that SPVD causes yield loss up to 80 - 90%. The disease was first reported in 1939 from eastern Belgian Congo (present Democratic Republic of Congo). SPCSV is crinivirus of Closterviridae and SPFMV is potyvirus belong to Potyviridae. SPFMV is transmitted by a wide range of aphid species. SPCSV is transmitted by white flies (Bemisia tabaci).

Management/Control

- Use healthy cuttings for planting.

- Remove the infected plants and burn them.

- Follow crop rotation.

- Spray suitable insecticides to control aphids and white flies.

Fusarium root and stem rot (Fusarium solani)

This is a fungal disease. Common symptoms are swollen and distorted base of stems. Deep, dark rot extending deep into root and forming elliptical cavities. Growth of white mold. Disease can be spread by infected transplants.

Roots of plants affected by root rot may turn from firm and white to black/brown and soft. Affected roots may also fall off the plant when touched. The leaves of affected plants may also wilt, become small or discoloured. Affected plants may also look stunted due to poor growth, develop cankers or ooze sap.

Management/Control

- Disease is generally not a problem if good sanitation is implemented.

- Select only disease-free roots for seed and transplant production.

- Use cut transplants rather than slips.

- Practice crop rotation.

- Treat seed roots with an appropriate fungicide prior to planting.

- Reduce wounding during harvest and post-harvest handling.

- Cut slips a minimum of 2cm above the soil surface to limit pathogen entry into wounds.

- Avoid planting in fields known to be infested with Fungus Solani

Enterprise budget for Crop - Sweetpotato 2020

Table below shows an estimated crop production budget for One Hectare Sweetpotato under Rain-Fed Condition. Computations have been done for some improved varieties as against the landraces.

Crop production budget for some improved sweetpotato varieties (2020)

| CRI-Patron | CRI- Ligri | CRI- Bohye | CRI-Dadanyuie | Local variety |

Gross benefits |

|

|

|

|

|

Average yield (t/ha) | 8.2 | 7.75 | 8.45 | 8.1 | 6.8 |

Adjusted yield (t/ha) | 7.4 | 6.98 | 7.61 | 7.3 | 6.12 |

Farm gate price (GHS/t) | 3,500 | 3,500 | 3,500 | 3,500 | 3,500 |

Total gross benefit (GHS) | 25,900 | 24,430 | 26,635 | 25,550 | 21,420 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Variable cost |

|

|

|

|

|

Cost of land hiring (GHS/Ha) | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

Cost of slashing (GHS/Ha) | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 |

Cost of planting material (¢/Ha) | 2,000 | 2,000 | 2,000 | 2,000 | 2,000 |

Cost of ploughing (GHS/Ha) | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 |

Cost of ridging (GHS/Ha) | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 | 1,000 |

Cost of planting (GHS/Ha) | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

Cost of weeding (GHS/Ha) | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 | 500 |

Cost of harvesting (GHS/Ha) | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 | 300 |

Cost transportation (GHS/Ha) | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 | 250 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total cost that vary (GHS) | 4,950 | 4,950 | 4,950 | 4,950 | 4,950 |

Net benefit (GHS/Ha) | 20,950 | 19,480 | 21,685 | 20,600 | 16,470 |

NOTE:

This budget does not include postharvest losses. The analysis is also general across the country with average price of inputs and does not consider glut and lean seasons in the computation of prices.

Average yield was adjusted 10% down to mimic farmers output if these varieties are adopted. Revenue generated is restricted to the sales of sweetpotato roots only and does not include vine cuttings.

Budget estimates is also based on discussions with Farmers and Research Scientists. Budget lines are applicable to all improved varieties.

Sweet Potato Crop Cycle

| Agro Ecology | JAN | FEB | MAR | APR | MAY | JUN | JUL | AUG | SEPT | OCT | NOV | DEC | ||

| Guinea Savanna Zone |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||

P | H |

| PP | P | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| CP/M |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||

| Agro Ecology | JAN | FEB | MAR | APR | MAY | JUN | JUL | AUG | SEPT | OCT | NOV | DEC | ||

| Coastal Savanna and Forest-Transition Zone |

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

PP | P |

|

| |||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

|

|

| CP/M | H | ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| ACTIVITIES | ||||||||||||||

| PP - Pre-planting (Land preparation) | ||||||||||||||

| P - Planting | ||||||||||||||

| CP/M - Cultural Practices/Maintenance (Weed control, Pests/diseases control, fertilizer application etc.) | ||||||||||||||

| H - Harvesting | ||||||||||||||

Agro-ecological Zones of Ghana

Policies and Programmes in Sweet Potato

Programmes

The following projects/programmes were formulated and implemented to support the production of food crops including sweetpotato in the country:

Root and Tuber Improvement and Marketing Programme (RTIMP)

RTIMP was funded by the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and the Government of Ghana for a period of 8 years (2007-2014). The goal of the programme was to enhance income and food security in order to improve livelihoods of the rural poor. The programme sought to build a competitive market-based root and tuber commodity chain supported by Market and Value Chain Analysis. Its programme components included the following:

- Support to increased commodity chain linkages;

- Support to root and tuber production;

- Upgrading of small-scale processing, business and marketing skills;

- Programme coordination, monitoring and evaluation.

The programme also supported the development and distribution of several improved varieties across the major production areas.

West African Agricultural Productivity Programme (WAAPP)

WAAPP was a two-phase, ten-year, horizontal and vertical adaptable programme lending to support the implementation of the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme’s (CAADP) agricultural research and development pillar, as reflected in the national agricultural investment plans and the regional mobilizing programme. The overall goal of the WAAPP was to contribute to agricultural productivity increase in the participating countries.

Ghana’s top priority crops focused on roots and tubers notably: cassava, yam, sweet potato and cocoyam.

The programme supported the CSIR-CRI to establish the Sweetpotato Programme at Fumesua which targeted to improve key traits of the crop such as dry matter content, beta-carotene content, starch yield, minerals, vitamins, sugars, fiber, pests and disease resistance. A major component of the programme was the facilitation of a reliable seed system, which ensures high and sustainable production of quality planting materials to enhance productivity of the crop. The promotion of these varieties through demonstrations and farmer fora is also undertaken to enhance adoption of the crop.

Specifically, the sweetpotato improvement program developed several varieties with the following attributes: high and stable yielding, disease and pest resistant (Sweet potato viral diseases and Cylas sp.); high nutritional and processing attributes (less sweet, high dry matter, high β-carotene, high starch and flour yield and consumer acceptable and preferred.

Planting for Food and Jobs (PFJ) campaign

This is one of the government flagships programmes which was launched in 2017. The objective of the campaign is to increase agriculture productivity and catalyze a structural transformation in the economy through increased farm incomes and job creation.

The campaign also seeks to motivate farmers to adopt certified seeds and fertilizers through a private sector-led marketing framework to raise the incentives and complementary service provisions on the usage of inputs, good agronomic practices, and marketing of outputs over an e-agriculture platform.

The programme is supporting farmers to access sweetpotato planting materials and other agro-inputs especially fertilizers at subsidized rates.

Other programmes and projects such as the underlisted have all contributed to the enhancement of the sweetpotato value chain the country:

- Demand Creation and Impact Scaling Project for Orange-fleshed sweetpotato funded by the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA).

- Orange: Healthy Gold for Ghana Project funded by CIP

- Jumpstarting OFSP Project funded by Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Other Sweet potato Resources

https://www.cbi.eu/market-information/fresh-fruit-vegetables/sweet-potatoes-0/market-potential

Comments

Post a Comment